This online exhibition features the research of Rose Ong'oa (pictured below), an Arkansas State University Heritage Studies PhD student. It was originally mounted at Arkansas State University Museum in honor of Black History Month (February 2008).

Introduction

This exhibition highlights the struggle of Swahili women, of slave descent, to cope with the challenges that have faced them since the abolition of slavery in East Africa in the late 19th century to the present. The lifestyle of the Swahili set them apart as a distinct African ethnic group as early as the 12th century; they lived in stone houses as opposed to the mud houses of other African peoples, they professed Islam, and owned slaves.

This exhibition highlights the struggle of Swahili women, of slave descent, to cope with the challenges that have faced them since the abolition of slavery in East Africa in the late 19th century to the present. The lifestyle of the Swahili set them apart as a distinct African ethnic group as early as the 12th century; they lived in stone houses as opposed to the mud houses of other African peoples, they professed Islam, and owned slaves.

Due to Swahili's long-standing social and political position, the British colonial government, in post abolition East Africa, favored members of the Swahili society, reserving certain types of rights only to members of this society. To access such rights, ex-slave women claimed Swahili identity, which entailed the command of Kiswahili language, and adherence to Islamic tenets. They created physical manifestations of their Swahili identity in their kanga clothing and managed to assert the legitimacy of the identity. In contemporary Swahili society, women continue to use kanga to challenge social, religious, and political ideals within their society.

Due to Swahili's long-standing social and political position, the British colonial government, in post abolition East Africa, favored members of the Swahili society, reserving certain types of rights only to members of this society. To access such rights, ex-slave women claimed Swahili identity, which entailed the command of Kiswahili language, and adherence to Islamic tenets. They created physical manifestations of their Swahili identity in their kanga clothing and managed to assert the legitimacy of the identity. In contemporary Swahili society, women continue to use kanga to challenge social, religious, and political ideals within their society.

This exhibition presents kanga--a type of cloth worn by women of Zanzibar in East Africa to assert their claim to Swahili identity and express socially taboo opinions in an acceptable manner.

This exhibition presents kanga--a type of cloth worn by women of Zanzibar in East Africa to assert their claim to Swahili identity and express socially taboo opinions in an acceptable manner.

Kanga was originally a plain white cloth imported from the United States in the 19th century. Worn by slaves in the US, it initially served the same purpose on the East African coast.

After the abolition of East African slavery in 1897, women sought to distance themselves from their slave past and align themselves with the freeborn Swahili. Boldly asserting a right to participate in Swahili society, they adopted the Moslem faith, learned Kiswahili (the language of the Swahili people), and began hand-painting their clothing with designs and proverbs long favored by free Swahili women.

In Swahili society today, women still find a voice in kanga to challenge social, religious, and political ideals--literally wearing what cannot be spoken.

Photos by Julie K. MacDonald, 2008

Creating a Swahili Identity

Kanga cloth documents the struggle of Swahili women of slave descent to assert the legitimacy of their claim to a free Swahili identity.

Kanga cloth documents the struggle of Swahili women of slave descent to assert the legitimacy of their claim to a free Swahili identity.

The lifestyle of the Swahili set them apart as a distinct African ethnic group as early as the 12th century. The Swahili lived in stone houses when other Africans lived in mud houses, for example, and they professed Islam, owned slaves, and were literate.

The British colonial government in post-abolition East Africa favored the Swahili by according certain rights only to members of this society. To access such rights, ex-slave women claimed Swahili identity, which entailed command of Kiswahili language and adherence to Islamic tenets.

As this exhibition demonstrates, the women also created physical manifestations of their Swahili identity in their kanga clothing--both motifs favored by the Swahili and proverbs written in Kiswahili.

Photo by Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Creating a Non-Swahili Identity

Slavery was abolished in East Africa in 1897, but its legacy--in part a divisive force, in part unifying--persists among the present-day peoples of East Africa. Swahili society encompasses both descendants of Swahili slave owners and the descendants of their slaves. The term Swahili, however, is often associated with a slave heritage.

As the women of slave heritage in Zanzibar seek to access Swahili identity, similarly, descendants of slave owners seek to separate themselves from their Swahili heritage altogether. For example, slave owners of Arab descent living in Zanzibar refer to themselves as Waarabu (Zanzibar Arabs). Others now refer to themselves as "the people of (their homeland)" such as these examples:

- People of Zanzibar (Wazanzibari)

- People of Ngazija, Comoro Islands (Wangazija)

- People of ShHir in Hadhramaut (Washihiri)

- People of Mvita, Mombasa (Wamvita)

- People of Lamu (Waamu)

- People of Pemba (Wapemba)

Ways of Wearing Kanga

Kanga is a convenient garment for Swahili women not only because it fulfills Moslem requirements for women's dress, but because it is relatively cheap and affordable to women of all classes.

Moslem female dress codes differ depending on whether a woman is at home or in public. Kanga may be readily adapted to suit the needs of a woman's daily activities, whether cooking, relaxing at home, working in the fields, attending a wedding, or deporting herself in mourning.

Dressed For A Wedding

Although kanga are worn as uniforms to weddings, Swahili women also adorn themselves in expensive jewelry and colorful Western-style clothing. To show off their jewelry and still protect their expensive Western clothing from dirt and harm, women wrap one piece of kanga around the waist and use the other piece as a decorative scarf thrown over the shoulders.

Dressed For Mourning or

Being "In Public"

When in mourning and even when simply in public, a woman must cover her body from head to toe. To do so, women wear kanga in pairs--one tied around the waist, and the other as a cape concealing the body from the head to just below the waist.

Dressed For The Kitchen

To ease movement and avoid accidents in the kitchen, women wear only one piece of kanga wrapped around the waist. They keep the second piece nearby in case they need to answer a knock at the door, in which case they will need to cover their head.

Dressed For Being At Home

Islam decrees that a woman's body may be observed only by her husband in the privacy of their bedroom. Here a woman is free to wear the slightest clothes--often a single kanga tied under the armpit with no other clothing underneath.

Dressed For the Fields

Even when working in the fields, a Moslem woman must cover herself in her voluminous cloths. To ease movement while working in the field, women may wear one piece of kanga wrapped around the waist. They tie the other piece on their heads to keep away dirt--and the eyes of passers by.

Photos on this page by Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Speaking Softly

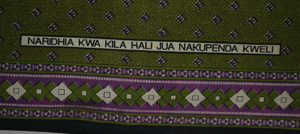

Traditionally, Moslem women must speak in soft, low tones, be polite, and be deferential to elders. The proverbs printed on these garments communicate feelings and opinions that would be offensive if spoken aloud. Through kanga, women challenge Islam's guidelines for gender-based decorum yet remain within the tenets of their faith.

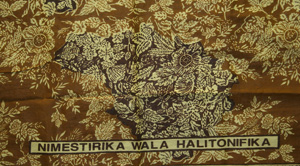

"I'm satisfied in all situations; just know that I love you"

"I'm satisfied in all situations; just know that I love you"

The owner of this kanga is the sole bread winner for her family. In keeping with Islam, Swahili men are expected to provide for the needs of their families. Fearing her husband felt inferior or insecure in their marriage, this woman chose a kanga softly assuring she loves him anyway.

"Let's be patient with one another and not fight over small things"

"Let's be patient with one another and not fight over small things"

The owner of this kanga wanted to help her husband see how trivial one of their disputes was. Since maintaining silence is a great virtue for women in Swahili society, men have an upper hand in making decisions, especially regarding family matters. Women can influence their husbands through messages in their kanga.

Wedding

Social gatherings present opportunities for women to share concerns, advice, and encouragement--and to correct one another without hurting feelings. Weddings are crucial settings for new in-laws to communicate. The mothers carefully select the kanga "uniform" family members will wear to send their message. The message itself may be intended for all attendants or for a specific target.

"Welcome, let's celebrate our children's wedding"

"Welcome, let's celebrate our children's wedding"

This wedding kanga was worn by a bride's side of the family. The message was general and meant for everyone. Marriage is the ideal course of life for Swahili women, and those who make lasting marriages earn society's respect. Weddings lay foundations for this respect.

"I'm protected and nothing evil shall befall me"

"I'm protected and nothing evil shall befall me"

The groom's side of this family selected their wedding uniform as a response to an insult from the bride's side of the family. As part of the wedding contract negotiations, the bride's family required the groom be tested for HIV. The groom's family felt the requirement implied immorality on the part of the groom and, by extension, accused his whole family.

Photos by Julie K. McDonald, 2008

Singing Our Minds

Zanzibar women love to express themselves through poetry. Many compose poems as a hobby. Some women perform their poems in songs during traditional dances or as entertainment during public events. Most kanga sayings now derive from such songs--with the song titles themselves appearing as kanga messages.

Bi Kidude (center) performs her poems in songs known both locally and internationally.

Bi Kidude gets ready for unyago--a traditional dance performed during initiation rites for young women.

Photos on this page by Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Wearing the Proverbs

The Swahili love proverbs and consider polite speech a prerequisite of competency in Kiswahili. An individual's ability to use tactful speech in strategic situations is a mark of intelligence.

Women masterfully take advantage of proverbs and euphemisms as gentle yet powerful means to admonish others--while earning respect from peers as competent, intelligent speakers of Kiswahili.

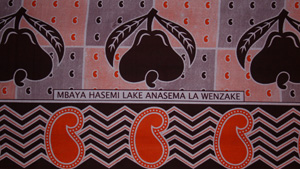

"An evil person does not talk about his/her evil deeds; he/she talks about other people's evils"

"An evil person does not talk about his/her evil deeds; he/she talks about other people's evils"

Swahili women chide bad behavior through the publicly acceptable medium of kanga cloth. In this example, a well known proverb advises people to beware when someone speaks ill of others. By wearing this kanga in the vicinity of a well known gossiper, a disparaged victim exacted a fitting revenge against her attacker.

"An enemy does not need a reason to harm you"

"An enemy does not need a reason to harm you"

This proverb alerts individuals to avoid sociopaths no matter how nice they may seem. Appearing on a kanga, this message could warn others of hypocrisy on the part of a particular person as well--and in a way that makes the identity of that person public knowledge.

Photos by Julie K. MacDonald, 2008

Heritage in our Clothing

Kanga cloth is dear to Swahili women because it depicts them as literate to observers. In Nungwi Village, kanga is the primary garment for women even though less than 5% of women in the village can read and write. Reported one informant (July 2007),

"We love kanga because it is our traditional garment. Our grandmothers used to wear it and they passed it to our mothers, our mothers passed it to us, and we shall pass it on to our daughters. It is a decent garment; it covers the body of a woman and preserves her dignity."

Nungwi Women Wearing Kanga

For over 100 years, kanga cloth has persisted as the favorite cloth for Swahili women. An average woman's active wardrobe includes at least 15 pairs of kanga.

Posing as Literate in Nungwi

The woman in the center is wearing her kanga inside out, so that the message is backwards. She may be unaware of it, possibly illiterate. This matters not, however, if her peers are equally illiterate and unable to reveal her secret.

Women at National Celebration for Zanzibar heritage

Kanga is the official outdoor garment for village women in Zanzibar.

Photos by Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Origins of Kanga Cloth

For newly freed women of post-abolition East Africa, the only garment readily available to them was the cheap white cotton cloth they had worn as slaves. Devoid of adornment and carrying the stigma of slavery, the old style garments put the women at a disadvantage in British-occupied Zanibar. A popular Swahili song of the early 20th century reflects the anxiety of the women:

"When did you become somebody? You came to the city wearing only a slave garment."

Using the only resource available to them, women began decorating their garments with hand-painted designs inspired by clothing of free Swahili women.

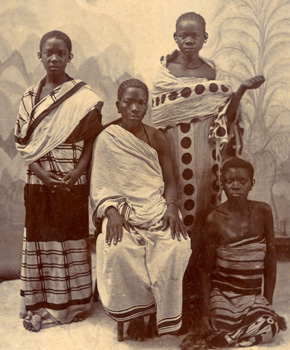

Traditional Swahili Woman's Slave Garment

Female slaves in Zanzibar dyed their clothes black to make them more feminine in accordance with Islamic sensibilities. They wore the cloth as a wrap tied under the arms.

Photo: Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 36.95

Embellishing the Slave Garment

This photograph shows the earliest development of kanga. Both women wear antecedents of kanga, draped in the style in which slaves wore their slave garments. The woman on the left wears the original slave cloth with no modifications. The woman on the right wears a hand-painted cloth with a border design resembling the border design on Portuguese handkerchiefs.

Photo: Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 53.54

Posing in Hand-Painted Kanga

These women wear hand-painted cloth draped in the style in which free women wore their clothing--one piece covering the upper body and another piece covering the lower body.

Photo: Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 31.62

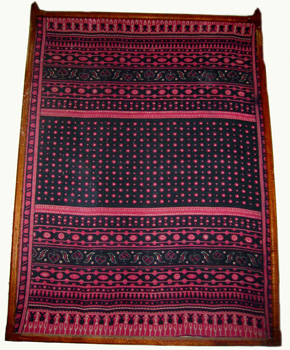

Early Kanga

Early kanga cloths bore no lettering. In the 1930s, a Kenyan cloth trader with an eye for marketing introduced proverbs to make the cloth more appealing to women.

Photo: Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Scripts of Kanga Messages

Kiswahili language was first written in the Arabic alphabet. Arabic is the language of the Quran; accordingly, the earliest kanga texts appeared in Arabic letters and carried religious themes. In the 1960s, Kiswahili preempted the Roman alphabet, moving the texts gradually towards the secular themes dominating kanga messages today.

Kanga With Written Messages

Written messages are today the single most identifying feature of kanga, yet the earliest examples had no sayings.

Kanga texts originated in the 1930s, when Haji Essak Abdulla Kaderdina, a cloth trader in Mombasa, Kenya learned of Zanzibar women's love of proverbs and their preoccupation with establishing a foothold in Swahili society. Seeing a market opportunity, he began printing a motto or proverb on the border of the cloth. The modern kanga was born and persists to this day--literally, a medium with a message.

Hand-Painted Kanga

Ex-slave women carefully painted their cloths by hand. This tedious and time-consuming job later inspired traders to produce block-printed cloths to satisfy the demand.

Photo: Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Servants of Princess Salma of Zanzibar

Floral motifs favored on kanga originated in patterned clothing of free Swahili women. Here the servants of Princess Salma of Zanzibar proudly model their clothing. As concubines of the Sultans and mothers to princes, royal servants were entitled to dress and be treated as free Swahili women.

Photo: Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 31.32

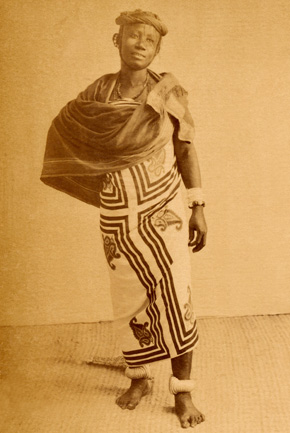

Handkerchief Garments

In the late 19th century free Swahili women commonly sewed together six imported Portuguese handkerchiefs to make a garment. The border design on these handkerchiefs inspired the border design of kanga.

Photo: Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 16.13

Technique

Designing Kanga Cloth

The women of East Africa saw plain white slave clothing as a canvas for embellishment and hand-painted it to suit their tastes and serve their social ambitions. Favoring floral motifs in general, they strategically selected examples long associated with clothing worn by freeborn Swahili women and hand-painted them on the cloth.

The paints for kanga designs were natural dyes extracted from henna and mdaa trees. The women pounded sun-dried barks and roots of the trees into powder and boiled it down to a brownish paste. After mixing the paste with black soot, they added coconut oil. Further boiling yielded a black, paste-like paint.

Motifs

Islam prohibits portraying human and animal figures in art, as they distract from contemplation of Allah (God). This extends to kanga and other textiles, as well. Accordingly, motifs derive from commonly recognizable images--mainly plants.

Women commonly decorate their kanga with jasmine twigs and rose flowers, since these are important ingredients of a favored facial scrub. The paisley-shaped cashew nut is a crop associated with wealth in the region.

Variations in Printing

Women experimented with printing techniques using materials readily available to them. According to oral tradition, 19th-century women dipped leaves into dye and used them like stencils; and they stamped designs with carved vegetables like potatoes.

To make a design against a dark background, women used resist-dye techniques. This entailed applying wax, oil, or other water-resistant substance to the cloth in the desired pattern and then dipping the whole cloth in a dye bath. The dye colored the background but would not "take" on the waxed designs. Removing the wax revealed a "white" or uncolored design.

Block-Printed (Stamped) Kanga

Hand-painted kanga enjoyed a wide popularity among ex-slave women. Market demand grew. In the late 19th century, local merchants with a penchant for profitable business began to make blocks with a wide range of kanga motifs carved into one end. Dipping the carved ends into dye and stamping the cloth with the designs, they were able to produce kanga in greater numbers.

Roller-Printed Kanga

Ex-slave women spent extravagantly on the block-printed cloths and in so doing caught the entrepreneurial eyes of foreign cloth manufacturers. British textile factories responded to this growing market in the early twentieth century by adapting the designs to roller-printers used in Britain and India for the mass-production of textiles.

The roller-printing technique deployed the designs onto the cloth even more quickly and efficiently and dramatically increased production of the lucrative textiles.

Technique (illustrated)

Woman at Henna Tree

This woman breaks a branch from a henna tree, one source of natural dye favored in kanga cloth.

Preparing Materials for Dye-Making

This woman pounds sun-dried barks and roots using a mortar and pestle.

Detail of Barks and Roots in Process

As pounding proceeds, the women assesses the product periodically for the desired fineness.

Woman With Winnowing Tray

The woman sifts larger pieces of barks and roots from the fine powder for further pounding.

Photos on this page by Rose Ong'oa, 2007

Progress vs Conformance

Swahili women of the present day are aware of alternate ways of life emanating from Western countries. Contact with the outside world inevitably brings the promise of progress . . . and the threat of change.

Some women advocate for the development of Swahili society toward a more Western lifestyle, while others promote traditional values and practices such as initiation rites and polygamy. Will women choose "progress" or conform? Their kanga follow the debate.

The Debate Over Feminine Decorum

Many women feel the attraction of progress. Some feel torn between worlds and attempt to negotiate between them. Others hold on to what they know and understand.

This is a debate with the potential to culminate into heated exchanges of words among the women; however, such confrontation in Swahili society is considered uncivilized behavior and a great source of shame. Through kanga, women engage in such arguments and take a stand without compromising civility.

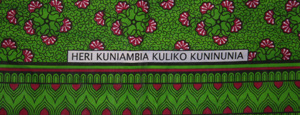

"Don't hold your grudge inside, tell me"

"Don't hold your grudge inside, tell me"

Swahili ideals encourage women to persevere and avoid confrontations; yet observance of such an ideal causes women to hurt inside and to hold grudges. The message on this kanga follows progressive thought, advising women to speak their minds and clear the air.

The Debate Over Education

A growing point of contention among women concerns new opportunities for education. Few women in Zanzibar have attained high school education, and even fewer have a college degree. Those who pursue an education may appear to others as status-grabbing snobs and become targets for gossip and slander.

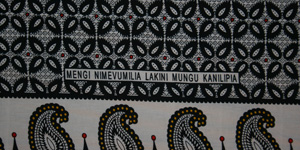

"I have withstood a lot, but God has paid me for it"

"I have withstood a lot, but God has paid me for it"

The owner of this kanga purchased it for her college graduation party to rebuke spiteful uneducated neighbors for their jealous slander. Rather than respond to their gossip while going to school, she waited until she graduated, invited all the women in her neighborhood to her party, and wore this kanga to show off her reward.

The Debate Over Polygamy

Islam permits men to have multiple wives--as many as four, so long as all wives receive equal treatment. Good Moslem women are expected to accept this tenet without question, yet women resent having to share their husband.

The number of men opting to invoke the right to multiple wives is unusually high in Zanzibar--a point of contention among women. To keep their men from taking second wives, most women revert to teachings they learned during traditional initiation rites: they conform to prescribed ways of making a happy marriage, practicing meekness in conduct, cleanliness, and good cooking skills.

"Don't compete with me, you can not win"

"Don't compete with me, you can not win"

With these words, a woman boasts and threatens a rival wife, saying her rival did not have what it takes to keep a man and will never get him back. The message derives from a popular song.

Hidden Messages

Traditional indigenous African practices--especially certain aspects of female initiation rites--are considered retrogressive in present day Moslem Zanzibar. Local government has enacted laws to prohibit objectionable practices, yet some women consider teachings given during initiation to be essential for successfully dealing with polygamy.

Women inclined to traditional ways, therefore, find their voice in kanga: they wear hidden messages to promote the old teachings without raising any alarm to the authorities against the practice.

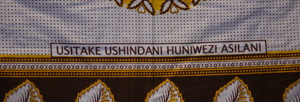

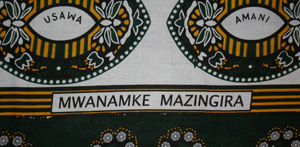

"Woman Environment"

"Woman Environment"

The text on this kanga is an incomplete sentence from a popular song that recites the teachings of unyago--an initiation rite for young women. The words "we want equality, peace, progress" in the central part of the kanga are deceptive: they suggest the kanga's wearer supports governmental ideals of progress, peace, and equality--including eradication of unyago.

The actual intent of the kanga's message is revealed in the words along the border: it is to promote tradition as clearly spelled out in the complete lyrics of the song. The slogan "Woman Environment" is, therefore, enigmatic to everyone lacking an insider's knowledge of both the whole song and the rites of unyago.

Photos by Julie K. MacDonald, 2008